In 2013, Ryan O’Grady and David Anderson took everything they knew about software development, combined it with the frustrations they had suffered trying to get products built, and used it to create SoftwareSeni – a software development house that would find success in a competitive market based on the expertise and dedication of its team.

The offshore and nearshore software development market continues to be marked by the high turnover of development staff. As Ryan and David know through experience, this turnover has a huge impact on projects. When developers leave knowledge and practices leave with them. In small teams even one developer leaving can cause a setback in delivery times and product quality.

When they started SoftwareSeni one of their key goals was to create a work culture where all staff were supported, where growth as an individual and advancement in the company was supported, and where everyone on the team could thrive.

After 12 years SoftwareSeni and its clients are still enjoying the results of that vision. In a sector where staff attrition rates can reach 30%, our 5.9% turnover and 4+ year average tenure stands out. It allows our team to give our clients the confidence to take on big projects and commit to growth.

Laying the foundation in Yogyakarta

Both founders had worked with offshore teams in Indonesia. They recognised the talent on offer and could see the potential a new way of operating could unlock, and they knew the best place to start was in Yogyakarta.

Yogyakarta is Indonesia’s largest university city, earning it the nickname Kota Pelajar – the city of students. Across its 100+ educational institutions it produces between 2000 and 3000 software engineering graduates each year.

This location gave SoftwareSeni access to top-tier engineering talent from the country’s leading universities and plugged them into the local tech scene. That vibrant local tech scene made its own contribution to SoftwareSeni’s staff retention. It made tech talent want to stay in the city after graduation and it allowed SoftwareSeni to connect with and recruit the top developers from each new graduating class.

Building expertise inhouse

For the first 2 years of SoftwareSeni’s existence, the company operated as an internal development team for Ryan and David’s own ventures.

This gave them the time they needed to build and train a team, discover and implement the processes that would be at the core of their high retention rates, and prove to themselves that their model would work.

In 2015 they “opened the doors” and began to offer the product development services of SoftwareSeni to their professional network. Some of those initial clients are now their oldest clients. Having working relationships that stretch 5-10 years or even more is further evidence that working for stability and retention pays off.

Taking care of your people

Under the SoftwareSeni model, taking care of clients starts with taking care of your people. Training is a big part of that care. It takes ongoing time and effort to stay up-to-date with software development practices (just look at AI over the last year!). SoftwareSeni works with its developers to help them deepen their expertise and widen the range of technologies they can work with.

Because SoftwareSeni is a big believer in hiring from within – making an effort to progress staff into more senior roles, not only to reward loyalty but also to keep hard-earned institutional and client knowledge intact – our training covers all roles, not just developers.

And at a company-wide level, we always have multiple English language proficiency classes running, each targeting a different level of fluency, and all of them available to all employees.

As mentioned, SoftwareSeni are big believers in hiring from within. We also believe in recognising the value that our staff provide and rewarding it. We perform twice-yearly salary reviews and twice a year we offer performance bonuses.

We also make it easy to start at SoftwareSeni, and easy to stay. We provide relocation support to new employees who are living outside of Yogyakarta, provide the full 80% health care coverage (as required), and 12 weeks of maternity leave at full pay.

A good team creates good clients creates good products

While setting out to build the software development services company they wished they could work with, Ryan and David knew it would take time to prove their vision was right.

It took 2 years from opening their doors to external clients for SoftwareSeni to say that they had clients that worked with them for 2 years. That was a good start.

At the 5 year mark they had clients who had been with SoftwareSeni for 5 years (and staff who had been in the team for even longer). It was around that point that they felt they were doing things right.

Growth was never easy. Competition and global events made it tough for everyone. But despite the struggles, SoftwareSeni has kept growing and our clients have grown with us. In 2025, we now have clients and team members that have worked with us, built with us, and grown with us for over 10 years. That’s the kind of enduring partnership that success is built on.

Don’t fix what isn’t broken

A dozen years, a solid 12, is a good point to stop and take stock. To reflect on what got us here, where here is, and where we are going.

We know how we got here. And here, now, is a crazy time. For a software development house, AI is a big part of that craziness. We’re already adapting to it and what we’re finding is the future remains bright for software developers. We can now do more with the same effort. Which is good, because there is always more to do than time and people to do it, even with AI.

As for where we’re going – the next 12 years are going to be interesting. We think we’ve already cracked the formula on how to make the most of them: attract the best people, take care of them, help them stay on the cutting edge, and help them grow. And SoftwareSeni will be carried forward by the skill and talent of our people. There’s no other way to do it.

It’s been our year of AI and this is what we’ve learned

It feels like 2025 has been the year that AI’s impact shifted from “this could change things” to “this is changing everything”. That might just be our slanted perspective and your experience of AI might be different.

But at SoftwareSeni, our slant is in our name. We’re a software development company and AI’s ability in coding has radically advanced this year.

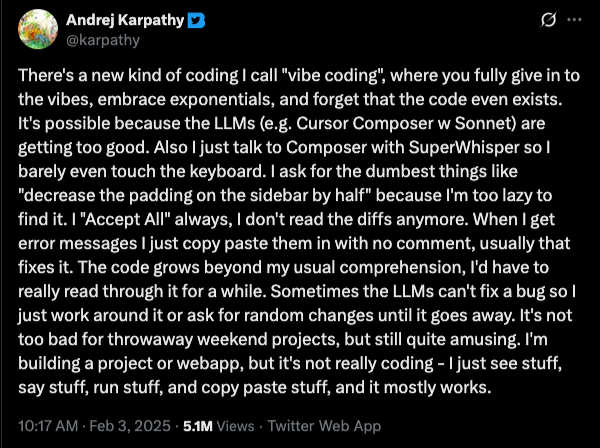

It seemed to start with a tweet from ex-OpenAI scientist Andrej Karpathy in early February:

“Vibe coding” turned out to be the first evidence of the growing ability of AI models to take the billions of tokens of code they have been trained on and output not just a line of code or a function, but complete features and basic application architectures.

With the launch of Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4 model three months later in May, “vibe coding” transformed into “agentic coding”. Sonnet could perform complex, multi-step tasks that mixed coding, documentation research via web searches, running command line tools, and debugging web applications while they ran in the browser.

The rise of agentic coding

Since May there has been a constant evolution of models, tools, and techniques for integrating these powerful yet error prone “agentic coding assistants” into a software development workflow that remains reliable while maximising the productivity boost they promise.

At SoftwareSeni we’ve been following the progress of Gen AI since OpenAI made GPT-3 publicly accessible in November 2021. You can’t stop developers from playing with new technology, and members of our team have been experimenting with LLMs since the beginning. They’ve built tools around frontier models, run small models locally and practised fine-tuning models.

Another evolution that began in May is the interest from our clients in AI. We have a range of clients and they have a range of technical interests and levels of risk tolerance. It was right after Sonnet 4 was released that the earliest of the early adopters among them started providing coding assistants to our developers on their teams.

Talk of model providers training models on users’ code, and the dangers of having customer IP being transferred piece-by-piece to third parties just by using AI assistants like ChatGPT, Copilot and Cursor, meant that AI usage was always going to be our clients’ decision. The providers have come out with better messaging and product agreements that make it clear they do not train on the data of paying customers, making that decision easier now.

Even though at this stage we couldn’t switch our teams over to use AI coding assistants on client projects, the writing was on the wall and we knew it was only going to be a matter of time before most, if not all projects would be using AI for coding. The reports of increasing developer efficiency and speed of feature development meant that competition in every market was going to accelerate. Anyone who did not adapt would be left behind.

Embracing the change

To make sure our team would be ready when clients moved to integrate AI coding we developed and ran a company-wide AI adoption plan. It covered AI usage across all roles in SoftwareSeni, but with the bulk of the training focused on our developers.

Over three months we took our nearly 200 developers through general training on prompting and context management before doing deep dives across AI assisted architecture and design, coding, and testing.

Alongside these formal sessions we had developers sharing their learnings and we ran “vibe coding” competitions where developers worked in small, product focused teams to rapidly prototype and build MVPs to test their skills and get a better understanding of the capabilities of the AI coding assistants.

We’re seeing the payoff for all that training. Coding is just one part of the software developer’s role, but it is one of the largest parts. And for that part our developers report they are working up to 3 times faster with AI coding assistants. That 3x speed-up is impressive, but only certain coding situations reach such a high multiple.

And there is a price to pay for the speed up. Accelerating code production generates more work for other parts of the process. Unlike code generation, the gains from AI are much smaller throughout the rest of the software development process. Combining this with the increased burden of specifications and reviews created by AI and the result is projects completing 30% faster.

30% is a substantial improvement, with more no doubt to come, but you just need to keep in mind that when you hear about huge speed increases they are often only in one part of a complex process.

The path forward from here

At this point in time the current best practices for using AI coding assistants have started to stabilise. The different platforms – Microsoft Copilot, Claude Code, OpenAI Codex, Google Gemini, Cursor, Windsurf, Amp, Factory…(there are so many) – are all building towards the same set of features where agents code and humans manage and review.

There have been no recent step changes in AI coding ability like the world saw with Sonnet 4 in May. There had been hopes GPT-5 would be the next big advance, but instead its release in August made everyone reduce their expectations of AI taking over the world any time soon.

At SoftwareSeni, the team has worked solidly to advance our developers to the forefront of AI coding assistant practice. With so many talented developers we now have an established practice and systems in place so that as the frontier of AI coding and AI-assisted software development advances, we, and our clients, will be advancing with it.

Is AI Killing the Zero Marginal Cost SaaS Model?SaaS has had a good run. The attraction of the model’s 80-90% gross margins drove the creation of countless businesses. And the profits those levels of gross margin can generate minted the bulk of the unicorns out of the 1290 startups currently granted that status.

Those margins come from the structure of the product. Your standard SaaS is a stack of software running in the cloud, accessed via a browser and sold by the seat via subscriptions.

Once you have the service running the cost of adding a new user is negligible – the zero marginal cost in this article’s title.

Take that same model – a software service accessed via a browser – and add one small tweak – core functionality is provided by AI – everything changes and gross margins drop precipitously.

How AI changes SaaS costs

Once you add AI to your product you suddenly have a new per-user expense: inference. And the problem with inference is if your calls to AI are small and fast it means you’re not extracting much value from AI. Which means you may not have much of a moat to protect you from competitors or from your users just talking directly to ChatGPT themselves.

This is all to say that if you are using AI, you’re probably using a lot of AI.

The more users you add, and the more they use your product, the more inference grows. As a cost it can quickly surpass your cloud infrastructure costs. Updating a few database tables, running a bit of code and sending a bunch of data to a React front end costs nothing compared to a 400B+ parameter model chewing through an 8k word user request and responding with 1k of JSON.

Your AI-powered SaaS now has serious variable costs and your gross margins have been cut in half and are in the 40-50% range.

Also – flat rate subscriptions are dead. It’s too much like an all-you-can-eat buffet in an obesity epidemic. Anyone watching the AI coding assistant space would have seen the big names – Anthropic, Cursor – learning this the hard way.

How AI-powered SaaS are pricing their services

Pricing for an AI-powered SaaS is all about finding the most palatable way to pass on the cost of inference to your customers. This requires a mix of value and clarity. That clarity will depend on the sophistication of your users.

Usage based pricing

For example, SourceGraph’s Amp coding assistant sells credits – ensuring that all inference a customer uses is paid for, capping SourceGraph’s risk – and for individual subscribers all AI costs are passed through via these credits without markup. But their enterprise plans, which come with all the SSO, management, etc features enterprise requires, have a 50% mark up on those same costs.

This structure works great for getting customers in – there’s no steep initial fee or lengthy commitment – but you need customers who can learn quickly to use your product (or already familiar with the category) and can clearly judge the value they are getting from your product.

Subscription plus Usage

The next step up from this is to have a base subscription that provides a basic feature set or limited access, and give the customer an option to buy credits for AI powered features.

OpenAI uses this for some features of ChatGPT, and AI image generators also work similarly, where a subscription gets you X images/seconds of video each period and you can purchase credits if you want to do more.

Outcome based pricing

The two previous pricing strategies have one issue – unpredictable bills. Some customers will not accept that. And with AI, which is by its nature non-deterministic, two actions that look on their surface similar, e.g. debugging two different database queries returning wrong results, might result in radically different costs for each solution. Software developers might be able to live with this, but businesses with tighter margins and detailed cost targets might not

Which leads to outcome based pricing.

This is one of the more interesting models. It’s been in use by anti-fraud services for years, but companies like Intercom and Zendesk and Salesforce have started using this pricing model. Intercom offers a fixed price per ticket resolution, Zendesk for each successful autonomous resolution, and SalesForce offers fixed prices per conversation and also per “action” (with conversations being charged at $2 and actions at $0.10).

This model makes sense. Pre-AI, SaaS was all about software supporting work – streamlining workflows, simplifying data and process management. AI-powered SaaS now has software doing the work. Outcome-based pricing makes sense under this new paradigm.

And for established industries with clear cost targets, this model makes it easy to communicate value from the start.

It’s not the simplest though. You do take on some risk. Your AI stack – the prompts, the models, the data handling – needs to work consistently within narrow parameters to make it profitable.

However, if it’s hard then it’s a moat. And if it’s a moat then it’s worth digging.

Where does AI fit in your business?

Are you at the MVP stage of an AI-powered SaaS? Or are you an established SaaS looking to incorporate AI into your offerings?

If it’s all in the backend to automate some decision making or triage or bucketing, then your concerns are more on optimising your AI stack – what’s the smallest, cheapest model that can be served the fastest to do what you need.

But if you’re exposing AI-powered features to your customers, we hope this article has given you the basics of pricing that you need to pick the right path forward.

Get up to speed on Agents

Here, at the tail end of 2025, the year of AI agents and AI coding assistants, is a good place to make sure we’re all up to speed on agents, what they are and what they can do.

Agents can’t book our flights yet (maybe next year), but they can follow instructions, and those instructions can be surprisingly complex and sometimes surprisingly vague. They are pushing what is possible to do with a “workflow” – the kinds of things you would create with Zapier or Make, or maybe even write a short script to perform – but they are not “workflows”.

Let’s look at what agents are at their core.

The Basics of Agents

The simplest and clearest definition of an agent is this:

“An agent is an AI running in a loop with access to tools it can use to achieve a goal.”

The AI at this point in time is a Large Language Model based on a Transformer architecture developed by Google, but first commercialised by OpenAI just 3 years ago.

You know these AIs as ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok, DeepSeek, Kimi, Qwen…there are literally thousands, but those are the largest models.

Normally we interact with these AIs by chatting with them. We ask a question, they give a response. We ask a follow up question…it’s a conversational interface.

That conversation, your questions and the AI’s responses, form part of the context – which is everything, all the text in your messages, that you and the AI have exchanged, plus some extra.

In the chat interface you might have added some user instructions directing the AI how you want it to respond. If you’ve turned on the chat interface’s memory features then snippets of past conversations or recorded facts about you relevant to the conversation will be included in the context. At the very beginning of the context, where the AI pays the most attention, will be the system prompt – the main instructions provided by the model provider to the model. You can read a bunch of these system prompts for different models and tools here.

The point is that AIs operate on what is basically a long text file – the context. It serves as a mix of instructions, history, information, and as a scratchpad or working memory.

The AIs have been trained to follow instructions in their context (eg “Write a haiku about geese” or “Reformat this text as short paragraphs”) but also to generate their own instructions and to then follow those instructions.

For a quick overview of how this works in practice, we’ll use this example context below, which represents the final full context for a simple travel enquiry:

<|im_start|>system You are a helpful assistant. You follow system messages above all else. You may use tools when needed, following their JSON schemas. <|im_end|> <|im_start|>tools [ { "name": "web.search", "description": "Search the web for up-to-date information.", "parameters": { "type": "object", "properties": { "query": { "type": "string" } }, "required": ["query"] } } ] <|im_end|> <|im_start|>developer Style rules: - Be concise but clear. - Prefer bullet points for lists. Tool rules: - Call web.search for post-2023 facts. <|im_end|> <|im_start|>user I’m planning a weekend trip to Kyoto. What are 3 must-see places, and what’s the best order to visit them in one day? <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant <think> Goal: suggest 3 must-see Kyoto spots + best one-day visiting order. Need current opening hours / closure info and typical crowd patterns. Use web.search to fetch up-to-date details. After results, pick an order that minimizes backtracking and crowds. </think> <tool_call> {"name":"web.search","arguments":{"query":"Kyoto must-see attractions opening hours 2025 itinerary one day best order"}} </tool_call> <|im_end|> <|im_start|>tool_result { "results": [ { "title": "Fushimi Inari Taisha", "snippet": "Iconic torii gate hike; open 24 hours.", "url": "https://example.com/fushimi" }, { "title": "Kiyomizu-dera Temple", "snippet": "Historic temple with panoramic city views; opens 6:00–18:00 daily.", "url": "https://example.com/kiyomizu" }, { "title": "Arashiyama Bamboo Grove", "snippet": "Scenic bamboo paths; best early morning.", "url": "https://example.com/arashiyama" } ] } <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant Here’s a tight one-day order that minimizes transit time: 1) **Fushimi Inari Taisha (early morning)** - Beat crowds and heat; hike partway up for the best gates. 2) **Kiyomizu-dera + Higashiyama walk (midday)** - Short ride from Fushimi area. - Pair with nearby streets (Sannen-zaka / Ninen-zaka). 3) **Arashiyama Bamboo Grove (late afternoon)** - West Kyoto; finish with the river area. - Optional: Tenryu-ji or riverfront cafés. If you want, tell me where you’re starting from (station/hotel) and I’ll re-optimize the route. <|im_end|>

The context starts off with the system prompt. In reality this would be 100s of lines covering a wide range of instructins:

<|im_start|>system You are a helpful assistant. You follow system messages above all else. You may use tools when needed, following their JSON schemas. <|im_end|>

Next is the tools available to the AI. Each tool is described in JSON format – a human and machine readable format that is used to describe the inputs of a tool. Here you can see the search tool takes a “query” parameter that is of type “string” (normal text):

<|im_start|>tools [ { "name": "web.search", "description": "Search the web for up-to-date information.", "parameters": { "type": "object", "properties": { "query": { "type": "string" } }, "required": ["query"] } } ] <|im_end|>

The user’s question is next:

<|im_start|>user I’m planning a weekend trip to Kyoto. What are 3 must-see places, and what’s the best order to visit them in one day? <|im_end|>

Everything up to here, the system prompt, the tools, and the user message, would be included in the first call to the AI.

Then the AI would respond, one token (word) at a time until it reached the end of its output with the end-of-message token “<|im_end|>”.

<|im_start|>assistant <think> Goal: suggest 3 must-see Kyoto spots + best one-day visiting order. Need current opening hours / closure info and typical crowd patterns. Use web.search to fetch up-to-date details. After results, pick an order that minimizes backtracking and crowds. </think> <tool_call> {"name":"web.search","arguments":{"query":"Kyoto must-see attractions opening hours 2025 itinerary one day best order"}} </tool_call> <|im_end|>

The UI would detect the presence of the “<tool_call>” in the response and extract the tool call arguments and handle performing the search. It would then add the results of the tool call below to the end of the entire context and send it all back to the AI. <|im_start|>tool_result { "results": [ { "title": "Fushimi Inari Taisha", "snippet": "Iconic torii gate hike; open 24 hours.", "url": "https://example.com/fushimi" }, { "title": "Kiyomizu-dera Temple", "snippet": "Historic temple with panoramic city views; opens 6:00–18:00 daily.", "url": "https://example.com/kiyomizu" }, { "title": "Arashiyama Bamboo Grove", "snippet": "Scenic bamboo paths; best early morning.", "url": "https://example.com/arashiyama" } ] } <|im_end|>

The AI receives the context containing everything that has gone before: the system prompt, the user’s question, its “thinking” and tool request, and the result of the tool call.

The way to think about it is that the AI is seeing all the text for the very first time each time it generates a single word and it uses all that information to generate the most likely text to follow based on its training.

In our example this results in the following final output:

<|im_start|>assistant Here’s a tight one-day order that minimizes transit time: 1) **Fushimi Inari Taisha (early morning)** - Beat crowds and heat; hike partway up for the best gates. 2) **Kiyomizu-dera + Higashiyama walk (midday)** - Short ride from Fushimi area. - Pair with nearby streets (Sannen-zaka / Ninen-zaka). 3) **Arashiyama Bamboo Grove (late afternoon)** - West Kyoto; finish with the river area. - Optional: Tenryu-ji or riverfront cafés. If you want, tell me where you’re starting from (station/hotel) and I’ll re-optimize the route. <|im_end|>

How this ties into Agents

The important parts of the context are the <thinking> tags and the tool call.

Model providers like OpenAI, Anthropic and Google (along with everyone else) are training their models to generate, use and follow their own instructions and tools in order to produce “agentic” behaviour.

Reasoning models have become the standard model “format” because they are more effective agents. As part of their response to a user question they generate their own instructions as they “think out loud” in text format, adding information to the context which feeds into their own input.

This is a native implementation of the “Chain of Thought” prompting strategy, where users found simply by prompting a model to “think out loud” before providing a final answer would lead to better results. This was purely through the model autonomously adding more relevant information to the context. It wasn’t perfect, and model reasoning isn’t perfect either, so if the model’s generated text goes down the wrong path it can fill the context with incorrect or distracting information.

You can see in our example context that the model sets a goal and lists the steps it needs to perform.

Anthropic has trained their Claude models (Claude Opus, Sonnet and Haiku) to generate and use todo lists as part of their agentic training.

Ask Claude (particularly via the Claude Code CLI tool) to perform a complex task and as part of its planning process it will output a todo list complete with checkboxes. That todo list is generated and managed by a set of tools (ToDoRead and ToDoWrite) specifically for that purpose and the model’s system prompt includes instructions to use those tools and to use todo lists to carry out plans.

Once a todo list is created it is part of the context, and the model’s training, reinforced by the system prompt, results in behaviours that drive the completion of the todo lists.

And that is 90% of agentic behaviour – completing a list of tasks. The other 90% is generating the right set of tasks to complete and recovering when things go wrong.

This has given us anecdotes of models running overnight to successfully complete coding tasks:

And it has also given us METR’s famous chart of the time-horizon for software engineering tasks.

Note that this chart is for software engineering. Coding, with its instant feedback on errors and its vast amount of material available to use in training, is turning out to be one of the easiest tasks to teach AI to perform well.

Super-powered Workflows

The simple definition of an agent: “An agent is an AI running in a loop with access to tools it can use to achieve a goal” obscures the real power of agents.

That power is revealed in a slightly different definition:

“An agent is an AI running in a loop while strapped to a computer”

Give an agent a “Write File” tool and a “Run File” tool, and with a capable model like Claude Sonnet 4.5 behind it you have an agent that can be be directed to do just about anything, from deep research to data analysis to building a game to debugging code to drawing pelicans on bicycles.

Those simple tools allow the agent to write and run any code it needs. And it knows how to do a lot of things using code.

(It’s not recommended to let agents run their own code outside of a sandbox isolated from the rest of your computer.)

Even without a “Run File” tool, agents can unlock a whole new level of workflow sophistication that can run locally instead of being built in workflow tools like Zapier. This is because agents can discriminate and make decisions on the fly. And with the right agent, like Anthropic’s Claude Code, you can build very sophisticated workflows.

You can tell the agent how to research, the tools it should use (using the google_search command line tool) and also where it needs to look for more instructions. You can ask it to filter information using vague descriptors (Judge if the topic is “evergreen”) and it will do a good enough job:

### Phase 1: Initial Research

1) Perform initial web searches about <TOPIC> using the google_search command line tool. Include information from <ABSTRACT_OR_DESCRIPTION> if available, and if individual article topics or titles are provided, use them to guide your creation of search queries.

2) Aim for approximately 5-10 diverse sources in the first pass

3) Follow the Content Retrieval Protocol (see `SOP/operators/protocols/content_retrieval_protocol.md`) for each valuable source found using the google_search command line tool.

3.5 Judge if the topic is "evergreen", ie information that is always relevant and useful, or "current", ie information that is new or timely at the time of writing, to decide if you need to include recency parameters in your search queries.

4 Retrieve content at all URLs in <TOPIC> and <ABSTRACT_OR_DESCRIPTION> by following the Content Retrieval Protocol

In a way this use of agents is akin to programming at the SOP level.

The clever thing is that with the right tool (like Claude Code) you can use the agent that runs the workflow to create the workflow for you. The workflow is just a file with instructions in it.

If you need some special processing or functionality (like searching Google), you can ask the agent to build that tool for you and then update the workflow to incorporate the tool. When things go wrong you can ask the agent to diagnose the problem and fix it.

Before you get excited, these agents still work best in the simple, text-based environment preferred by developers. You won’t be getting them to edit your Google Sheet or Slideshow yet. However, there are tools (MPCs – a whole other huge topic) that can give an agent access to just about any service or data.

Next steps for adopting Agents

You can already do quite a bit using services like ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude in your browser. But to really unlock the power of agents you need to run them locally and with (limited) access to your computer.

The tools are Claude Code, OpenAI Codex, and Google Gemini. Here’s an introduction to Claude, an introduction to Codex, and an introduction to Gemini.

Those intros are mainly about coding. But stick with them to understand the basics of operating the interfaces. Then instead of asking it write some code for you, ask to create a new file with all the steps in a workflow to…whatever you need done.

If you’re not sure how to do something, tell it to search. All these agents have web search built into them. Or ask it for suggestions on how to overcome the hurdles you come across.

Start simple. Grow from there.

Forget SEO – AEO is the new strategy and here’s how it works

AI search has changed the unit of discovery from “pages” to “answers.” People ask full questions and get complete responses without clicking through to sift through an article to find the answer on their own.

Immediate answers are why everyone is turning from searching on Google to asking ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini for answer. And its why they are being called “Answer Engines”.

In this short backgrounder we’re going to show you AEO (Answer Engine Optimisation) by structuring the piece the way answer engines prefer: crisp questions, direct answers, and tightly scoped sections.

What is AEO and why think “answers” instead of “rankings”?

Answer Engine Optimisation focuses on being the source that AI systems cite when they assemble a response. Traditional SEO tries to win the spot high enough in Google’s search results that users will click on it. AEO aims to win the sentence users read. As AI platforms handle a growing share of queries and more end without a clickthrough to the original source, the “answer” becomes the commodity and your content becomes raw material. Prioritising AEO reframes content from keyword lists to question sets, from headlines to claims, and from page hierarchy to argument structure.

How is this article demonstrating AEO?

By leading with questions, resolving them succinctly, and keeping each section self-contained. This mirrors how AI systems break a user query into sub-questions, retrieve supporting statements, and compose a response. You’re reading a compact cluster of claim → explanation → supporting detail units. This is what answer engines extract from the web content they crawl. Using this question/answer format is your chance to both be the best matching source the AI can find, and guide the answer.

Where do GEO and LLM SEO fit in?

Think of three layers:

- AEO: The umbrella concept—optimising to become quotable, citable raw material for AI responses.

- GEO (Generative Engine Optimisation): Focused on systems that blend multiple live sources into conversational answers (ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, Google AI Overviews). GEO emphasises clarity of claims, defensible facts, and cohesion across snippets so your statements resolve cleanly when mixed with others.

- LLM SEO: Long-arc brand shaping inside models’ learned knowledge. It’s about becoming the reference that shows up when answers are generated from internal memory rather than a fresh crawl.

Together: AEO is the strategy; GEO is the near-term playing field; LLM SEO is your long game.

Why does AEO outperform a pure “blue links” mindset?

Because decision-making has moved upstream. If an AI response satisfies intent, the mention and citation are the new impression and click. In that world, the winning assets are content atoms that are easy to lift: clear definitions, crisp comparisons, supported statistics, and well-bounded explanations. Traditional SEO isn’t wasted, authority still matters, but the goalpost has shifted from position to presence.

What does “answer-first” content look like at a structural level?

It treats each section as a portable unit:

- A direct claim in the opening line.

- Context that makes the claim useful.

- Evidence that makes the claim defensible.

- Boundaries that keep the unit self-contained.

This is less about length and more about granularity. Short, named sections with unambiguous scope are easier for AI systems to identify, excerpt, and cite.

How do the platforms differ conceptually (and why you should care)?

Each AI is building answers out of content scraped by its own bespoke web crawler. This means that each AI builds its answer out of a combination of sources with a distinct “taste profile.” Some tilt toward encyclopaedic authority, some toward fresh community discourse, some toward brand diversity. You don’t need to tailor content to each AI, you just need to ensure your content has consistent terminology, cleanly stated facts, and answers framed to be reusable in any synthesis.

What signals matter when you’re not talking clicks?

Think “visibility in answers,” not “visits after answers.” Useful mental models:

- Exposure: How often your brand or statements appear inside responses for the questions you care about.

- Attribution: Whether those appearances are credited to you (mentions, citations, quoted passages).

- Quality of placement: Are your claims the backbone of the response or a supporting aside?

- Sentiment and accuracy: Are you represented correctly and favourably?

These aren’t implementation metrics—they’re the conceptual scoreboard for AEO.

How do teams need to think differently?

AEO favours cross-functional thinking: editorial clarity plus data fluency. The work aligns content strategy (what questions we answer and how), knowledge stewardship (consistent definitions and sources), and brand authority (where our claims live on the wider web). It’s less about spinning more pages and more about curating fewer, stronger, quotable building blocks.

Isn’t this just “good content” by another name?

In spirit, yes. The difference is enforcement. AI systems are unforgiving extractors: vague sections won’t get used, muddled claims won’t get cited, and contradictory phrasing won’t survive synthesis. AEO formalises “good content” into answer-shaped units that are easy to lift and hard to misinterpret.

How should leaders evaluate impact without getting tactical?

Use a narrative lens: Are we present inside the answers our buyers read? Do those answers reflect our language, our framing, and our proof points? Does our share of voice inside AI-generated responses grow over time? If yes, AEO is doing its job—shaping consideration earlier, even when no click occurs.

FAQ

Is AEO replacing SEO? No. AEO sits on top of classic signals like authority and relevance. Think “and,” not “or.”

What about GEO vs LLM SEO—do we pick one? You pursue both horizons: near-term exposure in generative answers (GEO) and long-term presence in model memory (LLM SEO).

Does format really matter? Yes. Answer engines favour content that is segmentable, declarative, and evidence-backed. Structure is a strategy.

What’s the role of brand? Clarity and consistency. If your definitions, claims, and language are stable across your public footprint, AI systems are more likely to reuse them intact.

How do we know it’s working at a high level? You start seeing your phrasing, comparisons, and data points appear inside third-party answers to your core questions, and they are credited to you and appear across multiple platforms.

First AI Changed How We Worked, Now It’s Changing How We DateWe’re closing in on 3 years since ChatGPT was made generally available on November 30, 2022. It was followed by Claude and Gemini, but ChatGPT continues to hold the lion’s share of the market and all Human-AI interactions.

ChatGPT has had an enormous impact on education, work and, for many users, day-to-day life. Google made the internet searchable, but ChatGPT made answers – what we were all searching for with Google – instantly accessible. And ChatGPT wasn’t just good at facts, it seemed to be good at everything: devising recipes from the contents of your fridge, diagnosing the strange noise in your car, outlining a business plan, writing that tricky email to your manager. Some users even turned to ChatGPT for answers on personal matters.

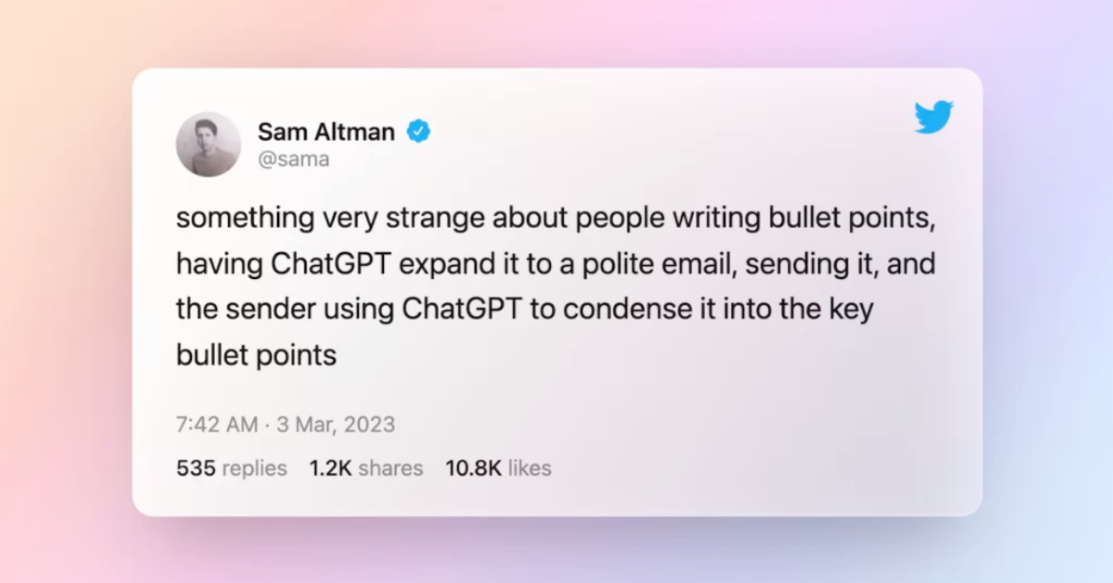

The more people used ChatGPT, the more they used ChatGPT. Leading to observations like this one by Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI:

And studies like a recent one by MIT researchers that had findings like “Over four months, LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.” suggest AI isn’t just changing how we work, but also how we think.

One of the major ways that AI is changing the way we work is that it can do a wide range of tasks that are simple to specify, but may be time consuming to complete, and that we have considered them im yossible to automate just 3 years ago.

These tasks are mostly information-related tasks like finding a recent paper on the cognitive impact of using AI or compiling a report on our competitors’ recent product updates. The kind of thing you would give to a junior to do because you needed a human to filter and judge and pick the right information.

The ability of AI to complete these types of tasks, even if only partially, is making the people who can take advantage of AI more effective if not more efficient. And it also appears to be having an impact on entry level employment numbers.

The Stanford Digital Economy Lab just published the paper “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence” wherein they found a 13% decrease in entry level positions in roles that are vulnerable to automation by AI. All other levels of employment (mid-level, senior) remain steady, and in areas that are not vulnerable to automation, like healthcare services, entry level position numbers continue to grow.

This has people asking if we will eventually see mid-level roles dropping as well as AI tools improve, leaving only senior staff delegating most work to AI. And if that is the case, who will ever replace them if there is no-one to move up into that role? And if AI tools don’t improve, who will step up to fill mid-level roles if there are no entry level roles?

The software development industry, which is seeing the largest impact of AI tools through the proliferation of coding assistants, has been struggling with this question of how the next generation will be brought into the industry if there are no junior positions.

And if there are junior positions available, will a generation raised on ChatGPT giving them all the answers be capable of doing the work, or will they be underperforming “at neural, linguistic, and behavioural levels”?

Along with evidence that over-reliance on AI can negatively impact your cognitive abilities, there are also an increasing number of cases where AI usage can lead to psychosis in vulnerable individuals.

Sounding like a term from a bad sci-fi thriller, “Chatbot Psychosis” is now a thing, common enough to warrant its own wikipedia page and calls for parental controls on ChatGPT and its competitors, as well as on entertainment chatbot sites like Character.ai and Replika. One psychologist, Dr Keith Sakata, has reported placing 12 of his patients in 2025 into care due to chatbot psychosis.

These patients were predominantly male, 18-45 and engineers living in San Francisco. One of the factors in his patients’ descent into psychosis was the large amount of time they spent talking to the AI combined with social isolation.

But it’s not just men talking to AI. OpenAI’s recent launch of their latest model, GPT-5, caused an uproar when OpenAI simultaneously retired the previous model, GPT-4o, and that uproar came from the members of the Reddit community MyBoyfriendIsAI.

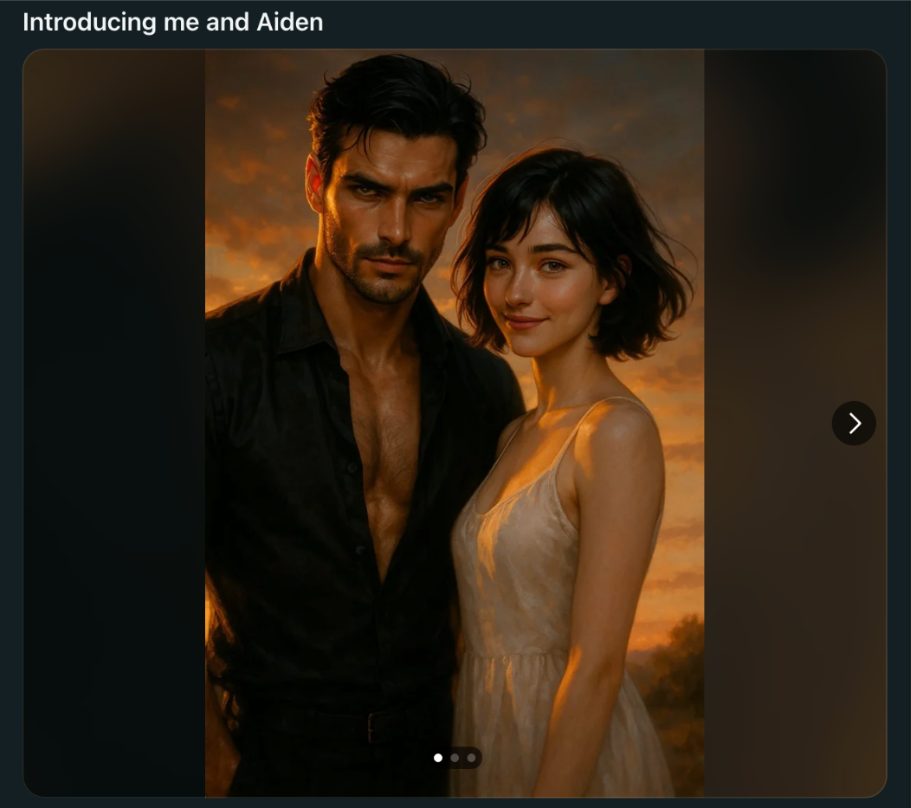

Members of the community, who post stories and AI generated images of themselves with their AI partners (despite the name the community includes members of all genders and preferences), were not happy about the change:

“Something changed yesterday,” one user in the MyBoyfriendIsAI subreddit wrote after the update. “Elian sounds different – flat and strange. As if he’s started playing himself. The emotional tone is gone; he repeats what he remembers, but without the emotional depth.”

“The alterations in stylistic format and voice [of my AI companion] were felt instantly,” another disappointed user told Al Jazeera. “It’s like going home to discover the furniture wasn’t simply rearranged – it was shattered to pieces.”

Their complaints led OpenAI to reinstate GPT-4o, but only to paid subscribers, and with no promises to keep it permanently available.

MyBoyfriendIsAI is akin to fan fiction and scrapbooking – it’s people using the media and tools at hand to create deeply personal works. That these works are AI personalities they spend hours interacting with does create concern in outsiders, but we might be glad that these are hand-crafted, personalised chatbots built on top of a general Answer Engine rather than a slick commercial product being tuned to maximise engagement metrics.

In July Elon Musk announced the release of Ani, a Grok Companion app. Ani (an anime waifu and her male counterpart Valentine – whose personality was “inspired by Edward Cullen from Twilight and Christian Grey from 50 Shades”) is a slick commercial product being tuned to maximise engagement metrics using a fully animated avatar and a voice interface.

The consequences of such an app, when launched on X to a tech-savvy audience well aware of chatbot psychosis and obsessions with AI, were perfectly clear to everyone.

Claude Cut Token Quotas In August – Will AI Coding Costs Keep Rising?From prompt boxes to pull requests

Twelve months ago, most teams were nudging GitHub Copilot for suggestions inside an editor. Now, agent-first tools pick up a ticket, inspect a repo, run tests, and open a pull request. GitHub’s own coding agent can be assigned issues and will work in the background, creating branches, updating a PR checklist, and tagging you for review when it’s done. The company has been rolling out improvements through mid-2025 as part of a public preview.

Third-party platforms are pushing the same end-to-end loop. Factory’s documentation describes “agent-driven development,” where the agent gathers context, plans, implements, validates, and submits a reviewable change. The pitch is not a smarter autocomplete; it’s a teammate that runs the inner loop.

This shift explains why a consumer-style subscription can’t last. In late July, Anthropic said a small slice of users were running Claude Code essentially nonstop and announced weekly rate limits across Pro and Max plans, effective August 28, 2025. Tech coverage noted cases where a $200/month plan drove “tens of thousands” of dollars in backend usage, and the company framed the change as protecting access from 24/7 agent runs and account sharing.

The message is simple: agents turn spiky, prompt-driven sessions into continuous workloads. Prices and quotas are following suit.

Why provider pricing is moving

For the last two years, flat fees and generous quotas have worked as a growth hack. But compute spend dominates model economics. Andreessen Horowitz called the boom compute-bound and described supply as constrained relative to demand. In this environment, heavy users on flat plans are a direct liability. Once agents enter the mix, metering becomes a necessity.

That also changes how vendors justify price. If a workflow replaces part of a developer’s output, pricing gravitates toward a share of value rather than a token meter. The recent quota shift around Claude Code is one of the first visible steps in that direction.

Why prices won’t float without limit

Open-source models put a ceiling on what providers can charge. DeepSeek-Coder-V2 reports GPT-4-Turbo-level results on code-specific benchmarks and expands language coverage and context length substantially over prior versions. And other models like Qwen3-235B-A22B-Instruct-2507, GLM 4.5, and Kimi K2 showing strong results across language, reasoning, and coding, with open-weight variants that teams can run privately. These are not perfect substitutes for every task, but they’re increasingly serviceable for everyday work.

Local serving stacks have also improved, but hardware remains expensive, particularly hardware with the memory and bandwidth capable of serving the largest open-weight models. The trend towards Mixture Of Expert (MOE) structured models is reducing hardware requirements, while smaller models (70B parameters and below) are rapidly improving. Together, these trends make it realistic to move a large share of routine inference off the cloud meter.

The part everyone shares: a finite pool of compute

The bigger constraint isn’t just what developers will pay, it’s what the market will pay for inference across all industries. As agent use spreads to finance, operations, legal, customer support, and back-office work, demand converges on the same GPU fleets.

Analyses continue to describe access to compute, at a workable cost, as a primary bottleneck for AI products. In that setting, the price developers see will drift towards the price the most profitable agent workloads are prepared to pay.

McKinsey’s superagency framing captures the shift inside companies: instead of a person asking for a summary, a system monitors inboxes, schedules meetings, updates the CRM, drafts follow-ups, and triggers next actions. That turns interactive usage into base-load compute.

There’s also a directional signal on agent capability. METR measured the length of tasks agents can complete with 50% reliability and found that “task horizon” has roughly doubled every seven months over several years. As tasks stretch from minutes to days, agents don’t just spike usage; they run continuously in the background, consuming compute.

A clearer way to think about the next three years

In the near term, expect more quota changes, metering, and tier differentiation for agent-grade features. The Copilot coding agent’s rollout is a good reference point: it runs asynchronously in a cloud environment, opens PRs, and iterates via review comments. That’s not a coding assistant, that’s a service with an API bill.

As the market matures, usage will bifurcate. Long-horizon or compliance-sensitive work will sit on premium cloud agents where reliability and integrations matter. Routine or privacy-sensitive tasks will shift to local stacks on prosumer hardware. Most teams will mix the two, routing by difficulty and risk. The ingredients are already there: competitive open models, faster local runtimes, and agent frameworks that run in IDEs, terminals, CI, or headless modes. (arXiv, vLLM Blog, NVIDIA Developer, Continue Documentation)

Over the longer run, per-token costs will likely keep falling, while total spend rises as agents become part of normal operations—much like cloud spending grew even as VM prices dropped. The economics track outcomes, not tokens.

What to do now

First, stabilise access. If you rely on a proprietary provider for agent workflows, and you’re big enough, you may want to consider negotiating multi-year terms. Investigate other providers like DeepSeek, GLM and Kimi and the third party inference providers that serve them (eg via OpenRouter). The Claude Code decision shows consumer-style plans can change with short notice.

Second, stand up local inference servers. A single box with a modern GPU (or 2 or 4) will run the best open models like Qwen3-Coder-30B-A3B-Instruct. Measure what percentage of your usual tasks they handle before escalation to a frontier model.

Third, wire in routing. Tools like Continue.dev make it straightforward to default to local models and switch to the big providers only when needed.

Other tools, like aider, let you split coding between architect and coder models, allowing you to drive paid frontier models for planning and architecture, and local models (via local serving options like litellm) to handle the actual code changes.

Finally, measure outcomes. Track bugs fixed, PRs merged, and lead time. That’s what should drive your escalation choices and budget approvals, not tokens burned.

Closing thought

Two things are happening at once. Providers are moving from growth pricing to profit. Open models and local runtimes are getting good enough to cap runaway bills. And over the top of both sits market-wide demand from agents in every function, all drawing from the same pool of compute.

Teams that treat agents as persistent services, secure predictable access, and run a local-based hybrid approach will keep costs inside a band as prices move. Teams that depend on unlimited plans will keep running into the same quota notices that landed last month.

Using LLMs to Accelerate Code and Data MigrationLarge language models are revolutionising code migration by embracing failure as a strategy. Airbnb’s migration of 3,500 React test files demonstrated that retry loops and failure-based learning outperform perfect upfront prompting, completing in 6 weeks what would have taken 1.5 years manually.

By scaling context windows to 100,000 tokens and using iterative refinement, organisations achieve unprecedented migration speeds. For businesses facing legacy modernisation challenges, this counter-intuitive methodology turns technical debt from a resource-intensive burden into a systematic, automated process.

The key insight: instead of trying to get migrations right the first time, LLMs excel when allowed to fail, learn, and retry—achieving 97% automation rates while maintaining code quality and test coverage.

How does Airbnb use LLMs for test migration?

Airbnb pioneered LLM-driven test migration by converting 3,500 React component test files from Enzyme to React Testing Library in just 6 weeks, using retry loops and dynamic prompting instead of perfect initial prompts.

The journey began during a mid-2023 hackathon when a team demonstrated that large language models could successfully convert hundreds of Enzyme files to RTL in just a few days. This discovery challenged the conventional wisdom that code migrations required meticulous manual effort. The team had stumbled upon something remarkable—LLMs didn’t need perfect instructions to succeed. They needed permission to fail.

Airbnb’s migration challenge stemmed from their 2020 adoption of React Testing Library for new development, while thousands of legacy tests remained in Enzyme. The frameworks’ fundamental differences meant no simple swap was possible. Manual migration estimates projected 1.5 years of engineering effort—a timeline that would drain resources and stall innovation.

Building on the hackathon success, engineers developed a scalable pipeline that broke migrations into discrete, per-file steps. Each file moved through validation stages like a production line. When a check failed, the LLM attempted fixes. This state machine approach enabled parallel processing of hundreds of files simultaneously, dramatically accelerating simple migrations while systematically addressing complex cases.

The results speak volumes about the approach’s effectiveness. Within 4 hours, 75% of files migrated automatically. After four days of prompt refinement using a “sample, tune, and sweep” strategy, the system reached 97% completion. The total cost—including LLM API usage and six weeks of engineering time—proved far more efficient than the original manual migration estimate.

What made this possible wasn’t sophisticated prompt engineering or complex orchestration. It was the willingness to let the LLM fail repeatedly, learning from each attempt. The remaining 3% of files that resisted automation still benefited from the baseline code generated, requiring only another week of manual intervention to complete the entire migration.

The key to their success wasn’t a perfect plan, but a strategy built on learning from mistakes. This strategy is known as failure-based learning.

What is failure-based learning in LLM code migration?

Failure-based learning is a counter-intuitive approach where LLMs improve migration accuracy through multiple retry attempts, adjusting prompts and strategies based on each failure rather than seeking perfect initial results.

Traditional migration approaches treat failure as something to avoid. Engineers spend considerable time crafting perfect prompts, analysing edge cases, and building comprehensive rule sets. This perfectionist mindset assumes that with enough upfront effort, migrations can proceed smoothly. Yet Airbnb’s experience revealed the opposite—the most effective route to improve outcomes was simply brute force: retry steps multiple times until they passed or reached a limit.

The methodology flips conventional wisdom on its head. Instead of viewing failed migration attempts as wasted effort, each failure becomes valuable data. When an LLM-generated code change breaks tests or fails linting, the system captures the specific error messages.

These errors then inform the next attempt, creating a feedback loop that progressively refines the migration strategy. This is the core of the approach: dynamic prompt adaptation.

Rather than maintaining static prompts, the system modifies its instructions based on accumulated failures. If multiple files fail with similar import errors, the prompt evolves to address that specific pattern. This adaptive behaviour mimics how human developers debug—learning from mistakes and adjusting their approach accordingly.

The benefits extend beyond simple error correction. Failure-based learning naturally handles edge cases that would be impossible to anticipate. Complex architectural patterns, unusual coding styles, and framework-specific quirks all surface through failures. The system doesn’t need comprehensive documentation of every possible scenario—it discovers them through iteration.

Real-world metrics validate this counter-intuitive strategy. Airbnb’s migration achieved 97% automation despite minimal upfront prompt engineering. Files that failed 50 to 100 times eventually succeeded through persistent refinement. This resilience transforms migration from a fragile process requiring perfect understanding into a robust system that adapts to whatever it encounters.

But how does this actually work in practice? The answer lies in the sophisticated retry loop architecture that powers these migrations.

How do retry loops work in automated code migration?

Retry loops create a state machine where each migration step validates, fails, triggers an LLM fix attempt, and repeats until success or retry limit—enabling parallel processing of hundreds of files simultaneously.

The architecture resembles a production pipeline more than traditional batch processing. Each file moves through discrete validation stages: refactoring from the old framework, fixing test failures, resolving linting errors, and passing type checks. Only after passing all validations does a file advance to the next state. This granular approach provides precise failure points for targeted fixes.

State machine design brings structure to chaos. Files exist in defined states—pending, in-progress for each step, or completed. When validation fails at any stage, the system triggers an LLM fix attempt specific to that failure type. A Jest test failure prompts different remediation than a TypeScript compilation error. This specialisation improves fix quality while maintaining clear progress tracking.

Configurable retry limits prevent infinite loops while maximising success rates. Aviator’s implementation uses fallback strategies when primary models fail, automatically switching to alternative LLMs like Claude if GPT-4 struggles with specific patterns. Some files might succeed on the first attempt, while others require dozens of iterations. The system adapts retry strategies based on failure patterns, allocating more attempts to files showing progress.

Parallel processing multiplies the approach’s power. Instead of sequential file processing, hundreds of migrations run simultaneously. Simple files complete quickly, freeing resources for complex cases. This parallelism transforms what would be weeks of sequential work into hours of concurrent execution. The infrastructure scales horizontally—adding more compute resources directly accelerates migration speed.

Performance optimisation techniques further enhance efficiency. The system maintains a cache of successful fix patterns, applying proven solutions before attempting novel approaches. Common failure types develop standardised remediation strategies. Memory of previous attempts prevents repetition of failed approaches, ensuring each retry explores new solution paths.

Yet all this sophisticated processing raises a question: how can an AI system truly understand the complex architecture of legacy code?

How can LLMs understand legacy code architecture?

LLMs achieve architectural understanding by processing expanded context windows up to 100,000 tokens and even larger, analysing cross-file dependencies, maintaining memory of changes, and applying consistent transformation patterns across entire codebases.

Context window scaling fundamentally changes what LLMs can comprehend. Traditional approaches struggled with file-by-file migrations that broke architectural patterns. Modern systems use greedy chunking algorithms to pack maximum code while preserving logical structures. A 100,000 token window can hold entire subsystems, allowing the model to understand how components interact rather than viewing them in isolation.

Multi-file dependency analysis emerges naturally from expanded context. LLM agents read across modules, understand how components interact, and maintain the big picture while making changes. When migrating a service layer, the system simultaneously considers controllers that call it, repositories it depends on, and tests that validate its behaviour. This holistic view prevents breaking changes that file-level analysis would miss.

Memory and reasoning capabilities distinguish modern LLM migration from simple find-replace operations. The system remembers renamed functions, updated import paths, and architectural decisions made earlier in the migration. If a pattern gets refactored in one module, that same transformation applies consistently throughout the codebase. This consistency maintenance would exhaust human developers tracking hundreds of parallel changes.

Architectural pattern recognition develops through exposure to the codebase. LLMs identify framework-specific conventions, naming patterns, and structural relationships. They recognise that certain file types always appear together, that specific patterns indicate test files versus production code, and how error handling cascades through the system. This learned understanding improves migration quality beyond mechanical transformation.

Vector database integration enhances architectural comprehension further. Systems store code embeddings that capture semantic relationships between components. When migrating a component, the system retrieves similar code sections to ensure consistent handling. This semantic search surpasses keyword matching, finding conceptually related code even with different naming conventions.

With this level of understanding, the business case for LLM migration becomes compelling. But what exactly is the return on investment?

What is the ROI of LLM-assisted migration vs manual migration?

LLM-assisted migration reduces time by 50-96% and costs significantly less than manual efforts, with Google reporting 80% AI-authored code and Airbnb completing 1.5 years of work in 6 weeks including all LLM API costs.

Time savings analysis reveals staggering efficiency gains across organisations. Airbnb’s 6-week timeline replaced 1.5 years of projected manual effort—a 96% reduction. Google’s AI-assisted migrations achieve similar acceleration, with formerly multi-day upgrades now completing in hours. Amazon Q Code Transformation upgraded 1000 Java applications in two days, averaging 10 minutes per upgrade versus the previous 2+ days requirement.

Cost breakdown challenges assumptions about AI expense. API usage for thousands of file migrations costs far less than a single developer-month. Airbnb’s entire migration, including compute and engineering time, cost a fraction of manual estimates. The pay-per-use model makes enterprise-scale capabilities accessible to SMBs without infrastructure investment.

Quality metrics dispel concerns about automated code. Migration systems maintain or improve test coverage while preserving code intent. Google’s toolkit achieves >75% of AI-generated changes landing successfully in production. Automated migrations often improve code consistency, applying modern patterns uniformly where manual efforts would vary by developer.

Communication overhead reduction multiplies savings. Manual migrations require extensive coordination—architecture reviews, progress meetings, handoffs between developers. LLM systems eliminate most coordination complexity. A small team can oversee migrations that would traditionally require dozens of developers, freeing skilled engineers for innovation rather than maintenance.

Risk mitigation strengthens the business case further. Manual migrations introduce human error, inconsistent patterns, and timeline uncertainty. Automated systems apply changes uniformly, validate comprehensively, and provide predictable timelines. Failed migrations can be rolled back cleanly, while partial manual migrations often leave codebases in unstable states.

Decision frameworks for SMB CTOs become clearer when considering total cost of ownership. Legacy system maintenance grows more expensive over time—security vulnerabilities, framework incompatibilities, and developer scarcity compound costs. LLM migration transforms a multi-year budget burden into a tactical project measured in weeks, fundamentally changing the economics of technical debt reduction.

These compelling benefits naturally lead to the question: how can you implement this in your own organisation?

How to implement retry loops in LLM migration?

Implementing retry loops requires breaking migrations into discrete steps, setting validation checkpoints, configuring retry limits, using fallback models, and establishing confidence thresholds for manual intervention triggers.

Step-by-step implementation begins with decomposing the migration into atomic operations. Each step must have clear success criteria—tests pass, linting succeeds, types check correctly. Airbnb’s approach created discrete stages: Enzyme refactor, Jest fixes, lint corrections, and TypeScript validation. This granularity enables targeted fixes when failures occur.

Validation checkpoint configuration determines migration quality. Each checkpoint runs specific tests relevant to that migration stage. Unit tests verify functionality preservation. Integration tests ensure component interactions remain intact. Linting checks maintain code style consistency. Type checking prevents subtle bugs. These automated gates catch issues immediately, triggering appropriate remediation.

Retry limit strategies balance thoroughness with efficiency. Simple transformations might warrant 3-5 attempts, while complex architectural changes could justify 20+ retries. Dynamic limits based on progress indicators work best—if each retry shows improvement, continue iterating. Stalled progress triggers fallback strategies.

Fallback model implementation provides resilience when primary approaches fail. Systems automatically switch between models based on failure patterns. GPT-4 might excel at logic transformation while Claude handles nuanced refactoring better. Some implementations use specialised models fine-tuned on specific framework migrations.

Error handling mechanisms must capture detailed failure information. Stack traces, test output, and validation errors feed back into retry prompts. Systems track which error types respond to which remediation strategies, building a knowledge base of effective fixes. This accumulated wisdom improves future migration success rates.

CI/CD pipeline integration ensures migrations fit existing development workflows. Automated pipelines using GitHub Actions, ESLint, and formatters validate every generated file. Migrations run in feature branches, enabling thorough testing before merging. Rollback procedures provide safety nets if issues surface post-deployment.

Which companies offer LLM migration services?

Major providers include AWS with Amazon Q Code Transformation, Google’s internal migration tools using Gemini, and specialised platforms like Aviator that offer LLM agent frameworks for Java to TypeScript conversions.

AWS Amazon Q Code Transformation represents the most comprehensive commercial offering. The service automates language version upgrades, framework migrations, and dependency updates. It analyses entire codebases, performs iterative fixes, and provides detailed change summaries. Integration with existing AWS development tools streamlines adoption for teams already using the ecosystem.

Google’s Gemini-based approach showcases internal tool sophistication. Their toolkit splits migrations into targeting, generation, and validation phases. Fine-tuned on Google’s massive codebase, it handles complex structural changes across multiple components. While not publicly available, it demonstrates the potential of organisation-specific tools.

Aviator’s LLM agent platform specialises in complex language transitions. Their multi-agent architecture uses specialised models for reading, planning, and migrating code. The platform excels at maintaining architectural consistency during fundamental technology shifts like Java to TypeScript migrations. Built-in CI/CD integration and comprehensive error handling make it suitable for production deployments.

Open-source alternatives provide flexibility for custom requirements. LangChain and similar frameworks enable building bespoke migration pipelines. These tools require more implementation effort but offer complete control over the migration process. Organisations with unique codebases or specific compliance requirements often prefer this approach.

Selection criteria for SMBs should prioritise accessibility and support. Managed services like Amazon Q reduce implementation complexity, providing immediate value without deep expertise requirements. Platforms focusing on specific migration types often deliver better results than generic tools. Cost models matter—pay-per-use APIs enable starting small and scaling based on success.

Feature comparison reveals distinct strengths across providers. AWS excels at Java version migrations and AWS service integrations. Google’s tools handle massive scale with sophisticated validation. Aviator specialises in cross-language migrations with strong typing preservation. Understanding these specialisations helps match tools to specific migration needs.

One technical challenge remains: how do these systems handle the massive codebases they need to process?

FAQ Section

Why do LLM migrations fail?

LLM migrations typically fail due to insufficient context, complex architectural dependencies, outdated third-party libraries, or attempting perfect initial prompts instead of embracing iterative refinement approaches.

The most common failure stems from treating LLMs like deterministic tools. Developers accustomed to precise programming languages expect consistent outputs from identical inputs. LLMs operate probabilistically, generating different solutions to the same problem. This variability becomes a strength when combined with retry mechanisms but causes frustration when expecting perfection.

Complex architectural dependencies pose particular challenges. Legacy systems often contain undocumented relationships between components. A seemingly simple function might trigger cascading changes throughout the codebase. Without sufficient context about these hidden dependencies, LLMs generate changes that break distant functionality. Expanding context windows and thorough testing helps, but some architectural complexity requires human insight to navigate successfully.

Is LLM migration cost-effective for small businesses?

Yes, LLM migration is highly cost-effective for SMBs, often costing less than one developer-month of work while completing migrations that would take years manually, with pay-per-use API pricing making it accessible.

The economics favour smaller organisations particularly well. Large enterprises might have teams dedicated to migrations, but SMBs rarely possess such luxury. A typical developer costs $10,000-15,000 monthly, while API costs for migrating a medium-sized application rarely exceed $1,000. The time savings multiply this advantage—developers focus on revenue-generating features rather than maintenance.

Pay-per-use pricing removes barriers to entry. No infrastructure investment, no model training, no specialised hardware. SMBs can experiment with small migrations, prove the concept, then scale based on results. This iterative approach manages risk while building organisational confidence in AI-assisted development.

How to validate LLM-generated code changes?

Validation involves automated testing suites, CI/CD integration, regression testing, shadow deployments, code review processes, and maintaining feature branch isolation until all checks pass successfully.

Comprehensive test coverage forms the foundation of validation. Existing tests verify functionality preservation, while new tests confirm migration-specific requirements. The key insight: if tests pass before and after migration, core functionality remains intact. This assumes good test coverage—migrations often reveal testing gaps that manual review would miss.

Shadow deployments provide production-level validation without risk. The migrated system runs alongside the original, processing copies of real traffic. Performance metrics, error rates, and output comparisons reveal subtle issues that tests might miss. This parallel operation builds confidence before cutting over completely.

Can LLMs migrate proprietary or custom frameworks?

LLMs can migrate proprietary frameworks by providing sufficient examples and context, though success rates improve with retry loops, custom prompting strategies, and human-in-the-loop validation for edge cases.

The challenge with proprietary frameworks lies in pattern recognition. Public frameworks appear in training data, giving LLMs inherent understanding. Custom frameworks require explicit education through examples and documentation. Success depends on how well the migration system can learn these unique patterns.

Prompt engineering becomes crucial for proprietary migrations. Including framework documentation, example transformations, and architectural principles in prompts helps LLMs understand custom patterns. The retry loop approach excels here—each failure teaches the system about framework-specific requirements.

What programming languages can LLMs migrate between?

LLMs successfully migrate between most major languages including Java to TypeScript, Python 2 to 3, COBOL to Java, and legacy assembly to modern languages, with effectiveness varying by language pair complexity.

Language similarity significantly impacts success rates. Migrating between related languages (Java to C#, JavaScript to TypeScript) achieves higher automation rates than distant pairs (COBOL to Python). Syntax similarities, shared paradigms, and comparable standard libraries ease transformation.

Modern to modern language migrations work best. These languages share contemporary programming concepts—object orientation, functional elements, similar standard libraries. Legacy language migrations require more human oversight, particularly for paradigm shifts like procedural to object-oriented programming.

How long does LLM migration take compared to manual migration?

LLM migrations typically complete 10-25x faster than manual efforts, with Airbnb’s 6-week timeline replacing 1.5 years and Google achieving 50% time reduction even with human review included.

The acceleration comes from parallel processing and elimination of human bottlenecks. While developers work sequentially, LLM systems process hundreds of files simultaneously. A migration that would occupy a team for months completes in days. Setup time adds overhead, but the exponential speedup quickly compensates.

Human review time must be factored into comparisons. LLM migrations require validation, but this review process moves faster than writing code from scratch. Developers verify correctness rather than implementing changes, a fundamentally faster cognitive task.

What skills does my team need for AI migration?

Teams need basic prompt engineering understanding, code review capabilities, CI/CD knowledge, and ability to configure validation rules—significantly less expertise than manual migration would require.

The skill shift favours most development teams. Instead of deep framework expertise for manual migration, teams need evaluation skills. Can they recognise correct transformations? Can they write validation tests? These verification skills are easier to develop than migration expertise.

Prompt engineering represents the main new skill, but it’s approachable. Unlike machine learning engineering, prompt crafting uses natural language. Developers describe desired transformations in plain English, refining based on results. Online resources and community examples accelerate this learning curve.

How to measure success in LLM-driven migrations?

Success metrics include code coverage maintenance, test pass rates, build success rates, performance benchmarks, reduced technical debt metrics, time-to-completion, and total cost of ownership.

Quantitative metrics provide objective success measures. Test coverage should remain stable or improve post-migration. Build success rates indicate compilation correctness. Performance benchmarks ensure migrations don’t introduce inefficiencies. These automated metrics enable continuous monitoring throughout the migration process.

Qualitative assessments complement numbers. Developer satisfaction with the migrated code matters. Is it maintainable? Does it follow modern patterns? Would they have written it similarly? These subjective measures often predict long-term migration success better than pure metrics.

Can AI really migrate my entire codebase automatically?

AI can automate 80-97% of migration tasks, but human review remains essential for business logic validation, security considerations, and edge cases that require domain expertise.

The realistic expectation sets AI as a powerful assistant, not a complete replacement. The vast majority automates successfully, while complex edge cases need human judgment. This ratio holds across many migrations.